Three Provocations for Community

Notes from the coliving conference

Groups often struggle with the same questions: how little structure is enough? How much conflict is too much? How open and accessible should we be? This essay explores these questions through small group discussions held at a coliving conference.

Last month I was invited to give a workshop at the Community Living Wisdom Exchange, an annual conference for community-builders held in San Francisco and organized by the Modern Family Institute.

I had spoken the previous year, presenting Chore Wheel as part of a series of lightning talks about internal systems.1 This time, I wanted to keep the narrative going: moving from systems to sensibilities and framing the workshop as a group exploration of the implicit expectations which often emerge in coliving settings.

The workshop, “Community Metaphysics” (see slides), came together as a fun and whimsical exploration of beliefs around technology, conflict, and affordability.

About 25 people participated, and everyone seemed to enjoy themselves. This essay records my notes from the workshop, summarizing the questions and main takeaways from each conversation.

The Setup

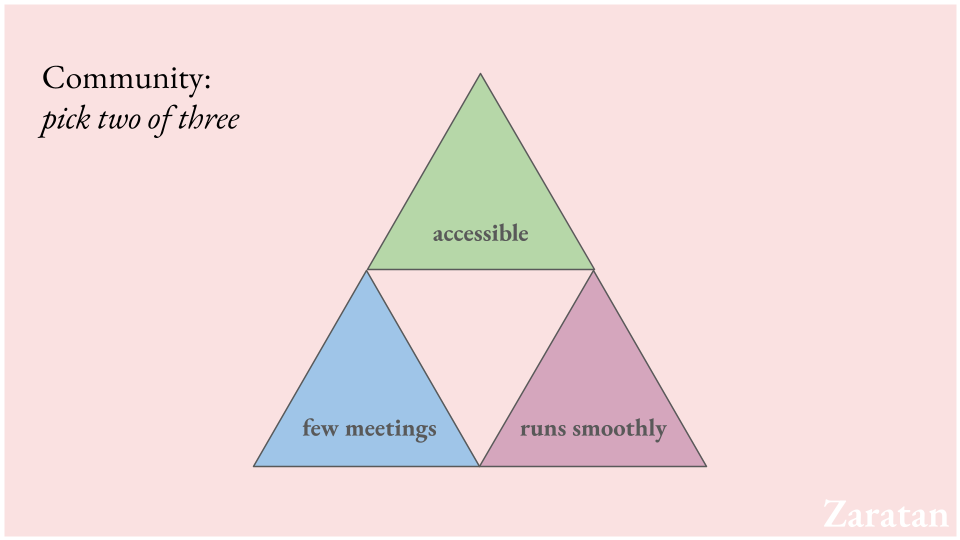

The workshop opened with some background on Zaratan — its motivations, guiding ideas, and early lessons. The problem is summarized in this slide, articulating an “inconsistent triad” of community living:

The contention is that communities are always navigating trade-offs between access, efficiencies, and outcomes. One can pay for services, raising the bar to entry; one can keep process lightweight, accepting more chaotic outcomes; or one can take on more work, increasing the risk of burnout. Each path carries risks which must be managed.

This framing is simplistic; experienced communities can achieve better outcomes than these trade-offs imply. But I do think (and others agreed) that this is a legitimate characterization of tensions which appear often among those living collectively.

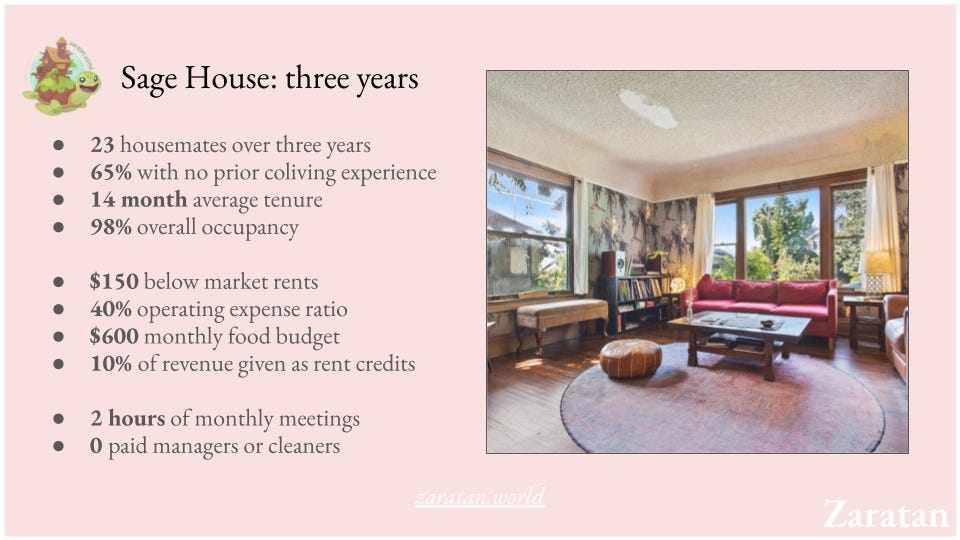

Chore Wheel was framed as part of a “new institutions” approach to community governance: helping communities get “three of three” through better structure and process. After seeing data from Sage House’s first three years, the audience seemed willing to entertain the argument.

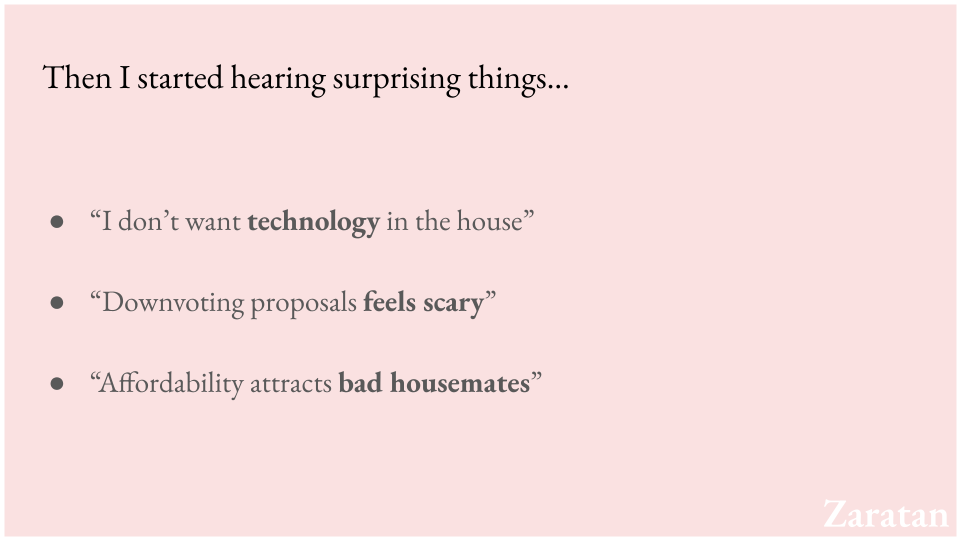

Setting up the workshop’s central questions, I shared some experiences talking to people about Zaratan and Chore Wheel, hearing similar questions and comments about technology, conflict, and affordability:

At first, this surprised me — surely community-builders would be as excited about new institutions as I was! But nearly six years after starting Zaratan, it’s become clear that it was my thinking which needed to evolve.

Ultimately, new tools are relevant only to the extent that an audience is culturally prepared to adopt them. The problem was no longer conceptual, but cultural: understanding the implicit social frameworks we are actually operating in.

With the setup complete, the workshop began. We spent about 15 minutes on each question: five minutes of frame-setting, five minutes of small-group discussion, and five minutes of whole-group sharing.

About Technology

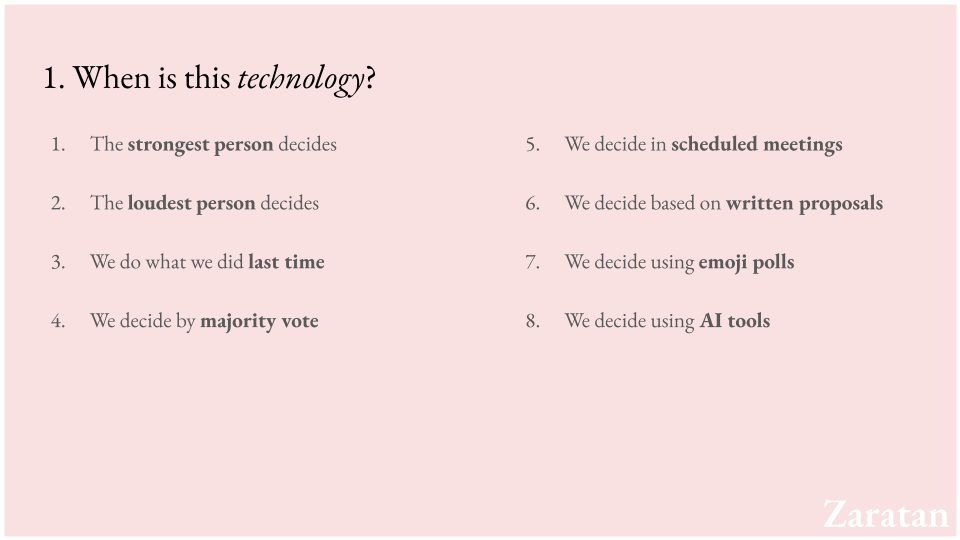

The first provocation was about technology. In “The Magic Circle,” I showed how many are drawn to coliving out of a romantic desire to create a sacred space of relationality — which often seems to involve the rejection of “technological” structures for mediating those relationships.

My contestation is that “technology” here is being conceptualized only partially, as digital technology only, when in fact technology can be understood more broadly as tools for processing information. These communities in fact are using “technology” without calling it such, and are thus drawing a somewhat arbitrary and limiting line.

The goal of this provocation was to encourage the audience to conceptualize technology more broadly, and to see digital technology less as a distinction of kind, but rather of degree — as a useful evolution in our ability to communicate.

The discussion surfaced valuable take-aways. The most important was that people are not resistant to technology per-se, but rather to the kind of intrusive and controlling internet technology which over the last twenty years has come to dominate our public sphere. This evolution, recounted by Shoshana Zuboff in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, has been the subject of substantial inquiry and is one of the key social and economic dynamics in contemporary American life.

Having spent time in radical political and technological circles, I was familiar with these critiques. Over the years, my views on technology have come largely in line with those of countercultural figures like Stewart Brand, who through the Whole Earth Catalog advocated for liberating “soft technologies” expanding human agency.

Most of my career has been spent designing such tools — and with it, developing an appreciation that their impact depends as much on cultural climate as it does on the tools themselves. Listening to the discussion of the participants, it was clear that the techno-optimism of the ‘60s is gone, and new technologies will need to answer not only for themselves, but for decades of promises broken by others.

About Conflict

Next came conflict. As I discuss in “The Boundaries of Belonging,” the way communities handle conflict largely determines their long-term outcomes. There is a tendency among those new to communal living to avoid conflict; as they gain experience, they increasingly understand the importance of conflict management.

This conversation revolved around the work of Frederic Laloux, who wrote the popular Reinventing Organizations about self-managing organizations. For Laloux, conflict management is one of an organization’s most important capacities — but it is also one that participants must ultimately learn by doing. While technology can make this easier, there is no substitute for the willingness to hold somebody accountable.

During the discussion, the participants expressed fairly positive views about conflict. For many of them, conflict was seen as a way to get closer to somebody; by confronting and resolving disagreements, people come to know each other on deeper and deeper levels.

What people did not like, however, was unstructured conflict — which makes sense. From philosophers like René Girard to biologists like George R. Price, scholars across disciplines have understood the importance of structure and ritual in containing conflict within socially productive bounds. Groups able to structure conflict enjoy greater generativity and adaptibility to changing conditions; groups which cannot are likely to implode under stress.

There are many ways to structure conflict — through appeals to authority like an owner or manager, through peer accountability processes like those advocated by Laloux, or with the aid of tools like Chore Wheel, which offer structured pathways for resolving conflict. There is no right answer, only the right answer for you — and the participants (an admittedly self-selected crowd) seemed to intuitively grasp this.

About Affordability

Last, we turned to affordability. As I argued in “The Tragedy of Microapartments,” coliving is one of the best paths towards large-scale housing affordability in this country. Having come up through the leadership of Berkeley Student Cooperative (BSC) and then the North American Students of Cooperation (NASCO), coliving and mutual aid are for me fundamentally intertwined, with community emerging organically through shared effort.

But not everybody sees it this way. Through conversations and getting to know people inside of the “meta-community” (the community of people working on community), I’ve found that affordability is often at best a nice-to-have, and certainly not the goal of the collective effort.

This discussion was framed through the image of the “Rubin Vase,” an optical illusion featuring an ambiguous figure and ground. Are we looking at a vase, or at two faces?

Not all the participants accepted the framing. Some said it was a “false dichotomy” and that you could indeed have both community and affordability. This is certainly true — and often you do. But if something had to give, what would it be?

To my surprise, most of the participants came down on the side of community. The goal of the conference attendees was to build a more relational life for themselves, and were in many cases willing to put in extra effort, in both time and money, to achieve this goal. When affordability emerged, as it often did through shared food purchasing or tool use, it was seen as a nice to have, not a sine qua non.

A second undercurrent emerged: for better or worse, those able to pay more were often preferable to live with, being typically more highly educated and socially connected. It is arguably more important to consider the inverse: that those looking for cheap rooms are more likely to exhibit anti-social tendencies. There is nothing inherently wrong with using price and positioning as a way to filter for community members, but I do believe this approach limits coliving to a niche lifestyle choice for the affluent or well-connected. For coliving to play a larger role in America’s housing landscape — increasingly important as rising generations face the reality of downwards mobility — affordability will need to be emphasized.

After the session, a fellow NASCO alum took me aside and confided a subtler reality: that much of the Bay Area coliving world runs on a tacit network of patrons, who subsidize community houses out of a personal generosity.2 Without connections to wealth networks, many of these houses might not even exist. Again, there is nothing inherently wrong with this — but it is important context.3

Conclusions

Overall, the workshop was useful for me and well-received by the participants. Some observed (correctly) that all three questions were quite leading (which they were), but that they had nonetheless enjoyed the discussion and found it thought-provoking.

The experience deepened my understanding of the views and values of an important subset of the coliving world, for whom community is an end in-and-of-itself, and for whom creating a refuge from the modern world is as important as trying to innovate within it. My conviction in Zaratan’s approach of making tools that are both powerful and human, and of making community more accessible through institutional design, has only grown stronger after engaging with these tensions more directly.

Civilization is part technology and part culture, and while technology advances in fits and starts, culture advances one conversation at a time.

My talk had apparently been memorable, less for the content and more for the fact that it followed immediately after a talk arguing against chore systems. It was funny, if awkward.

Stereotypically, “rich burners” — for whom sponsoring a coliving house confers social status analogous to owning a popular restaurant.

Sage was built with a mixture of debt and equity and has been a moderate financial success. Broadly, I believe that for coliving to become more accessible it must become more legible to capital.

Interesting. I agree with a lot of the conclusions - I am yet to find a single co-living spaces of any size that manages kitchen conflicts well, and they who figure it out will be in high demand!

Did your group discuss creative output of co-living spaces? It’s something that interests me, take a look at my recent post and let me know what you think.

https://heidiwarwick.substack.com/p/reimagining-co-living-as-cultural