Two Months at SettleLiving

Reflections on a fly-by-night coliving operation

Editors note: our recent piece, The Tragedy of Microapartments, earned a thoughtful response from Brad Hargreaves, founder of Common and editor-in-chief of Thesis Driven, one of the country’s premiere real estate blogs. You can read his response here.

Earlier this March, I found myself back on New York City’s housing market. I had just ended a three-year relationship, and needed a new place to live.

Leaving my partner’s Greenwich Village apartment, I was lucky to be welcomed in by my uncle and his family on the Upper West Side. During the few weeks that I stayed with him, I scoured WhatsApp groups, Discord servers, Craigslist, and a motley of other sources to try and find a permanent new place.

After six weeks of searching, including some false starts and dead ends, I found myself in a two-month sublet in a four-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. The apartment was managed by a company called SettleLiving, which rents whole units then sublets individual rooms through a coliving model.

Having spent the last five years running Zaratan Coliving as a mostly solo founder, I thought it would be a good opportunity to see how other people did things.

The rest of this essay will talk about my experience navigating the housing market and spending two months at Settle.

The Housing Market

While staying with my uncle, I spent many hours per week searching for housing. My first stops were the existing networks for community housing in NYC. I would regularly check Discord servers and WhatsApp groups, letting folks know I was looking and exploring inventory on offer. I think I’m easy to live with — curious, conscientious, empathetic — and was optimistic about what I’d find.

Overall, I was disappointed. Coliving rooms were expensive — I was offered a lofted bed in Bushwick for $2,000 per month, and an 80 sqft room in Boerum Hill for about the same. More upscale coliving houses had rooms starting at $2,500 and going up to $4,000 or more — roughly the price of a one-bedroom in Chelsea. As someone who thinks a lot about housing affordability — and sees coliving as one of the best paths toward it — the lack of “affordable” options was striking.1

The most affordable option I found was a bohemian commune, which offered me a room in a converted kitchen for $1,500 plus a $400 community fee and eight hours of monthly chores and meetings. They expected me to practice radical honesty and told me that my first three months would be “probationary” while they decided whether I was a good fit long-term. Even for someone who believes strongly in process, that level of ritualized vulnerability — and prospect of eviction — felt intense.

My Craigslist experience wasn’t much better. The pricing improved — beds ranged from $1,200 – $1,800 — but communication was awful. I encountered one obvious scam, but mostly people were just flaky. The majority of emails I sent got no response, or I’d get ghosted in the middle of a text exchange. The few places I did visit were uninspiring; I wasn’t desperate.

Eventually, I found a long-term place I was happy about, run by one of New York’s “corporate” coliving companies. They had a web presence, good communication, nice spaces, and fair prices. I was able to find a building in my preferred location of Clinton Hill, walking distance from my new job. There was one catch — the room wasn’t available for two more months.

Not wanting to restart my entire search, I turned to Settle.

Moving In

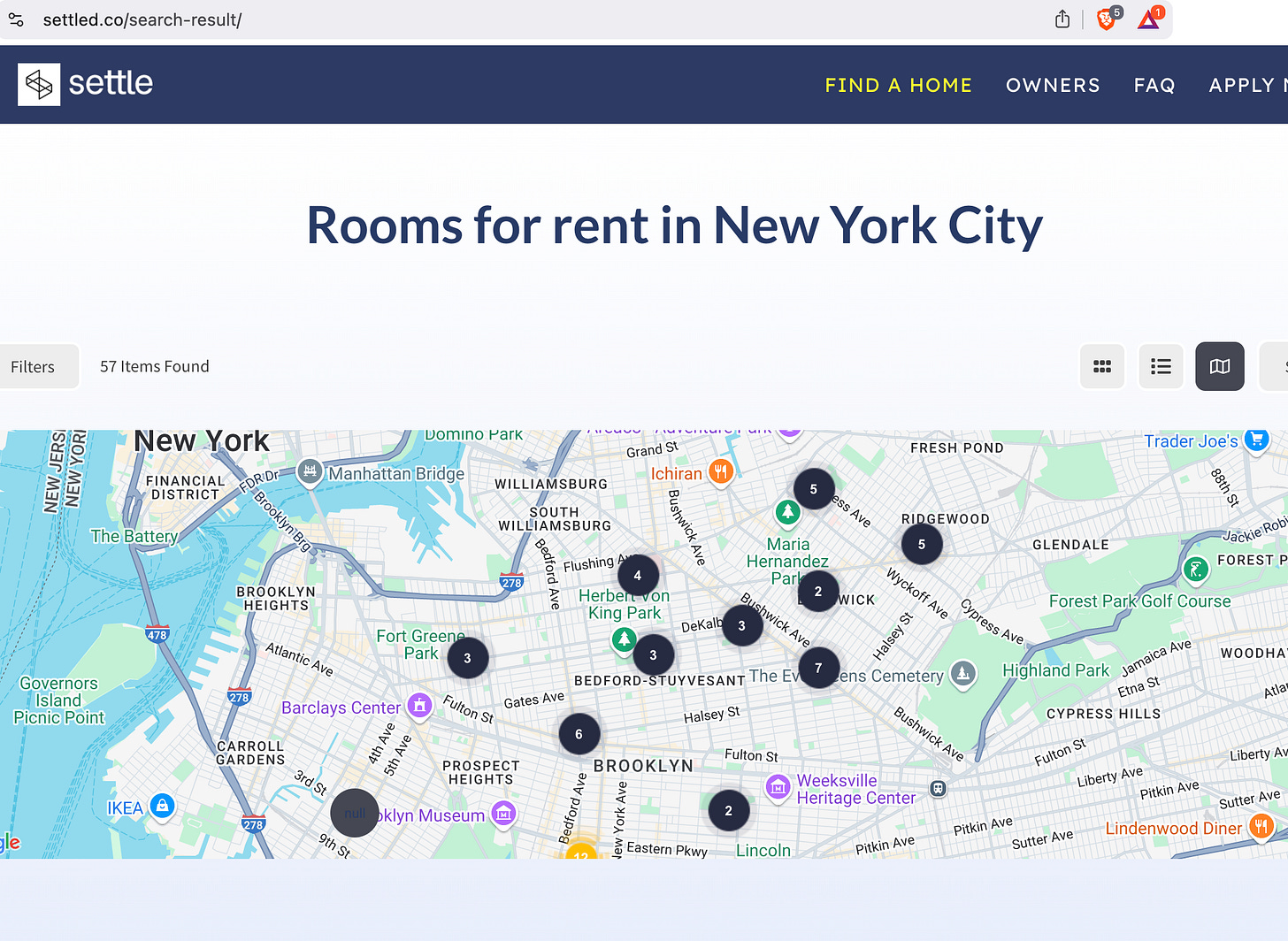

Similar to the first operator, Settle had a website where I could search for rooms by location, and see pricing up-front. This made it easy to find a room I wanted and to start a conversation. Having spent several weeks combing through group chats and getting ghosted on Craigslist, that value proposition had never felt more clear.

The application and leasing process was standard, if a bit quirky. After reaching out through their website, I had a Zoom call with one of their staff, a friendly Filipina woman who I assume lived abroad. Less than ten seconds into the call, she asks me point-blank: “are you crazy?” I would later find this was common practice for Settle. Unconventional screening technique or housing law violation — you be the judge.

After passing the “screening” I was sent a lease, which was pretty standard, with some charming color:2

It was clear to me what SettleLiving was: a capital-light subleasing operation, where the company takes out long-term leases on class-B apartments, furnishes them, and then ekes out a margin by offering month-to-month sublets at marked-up prices — with rent paid via PayPal.

My impression had not been of sophistication, but it had not been of fraud either — and to their credit, the room was well-priced, sub-$1,500 including utilities. I needed a place, and thought that if nothing else, it would be a good learning experience to see how other people did things. I signed up.

Life at Settle

The apartment was a third floor walk-up on a lively stretch of Bedford Avenue, with four bedrooms (one of which was a converted study) adjoining a windowless living room and kitchen, all sharing a single bathroom. The living room was plain, the knives were dull, the bathroom was cramped, and the rooms were 90 square feet:

My roommates were three women in their mid-twenties: two Irish girls on work visas, and a redheaded actress from Arkansas. They were friendly and welcoming, and we developed an easygoing rapport — over the next two months, I would hear many stories of the Irish girls’ happy-hour escapades and the redhead’s evolving polycule.

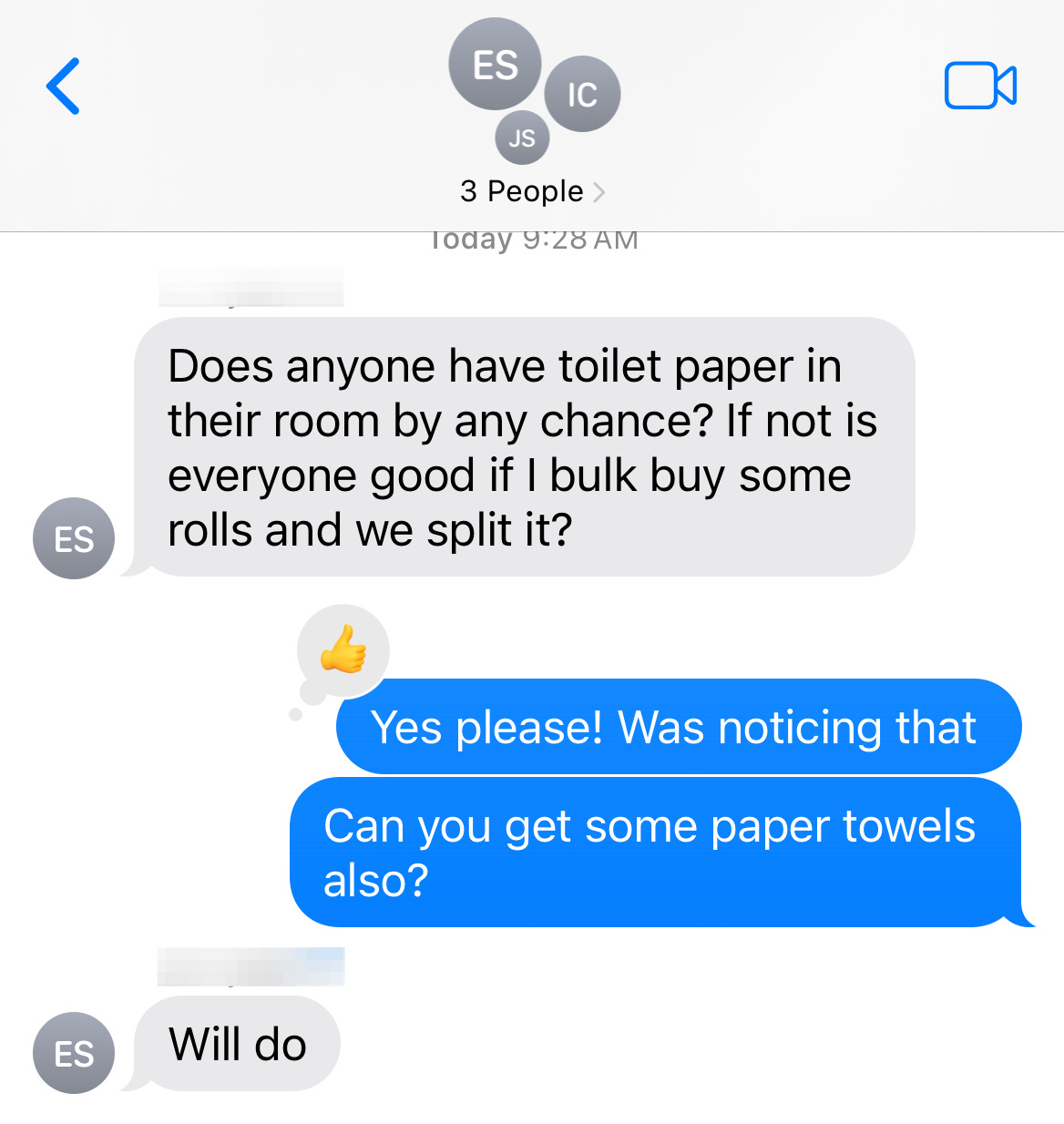

There was no meaningful structure among the roommates — folks would clean up, take out the trash, and buy supplies whenever they saw fit. There were only four of us, and everyone was fairly conscientious, so it worked out fine — but it was definitely a “reactive” style of organization. Everything was ignored until someone cared enough to deal with it, and things nobody cared about were never done. The result was a slow accumulation of grime and periodic shortage of toilet paper:

I rarely used the kitchen and spent most of my time in my room. About once a week I would run into some of my roommates and we’d have a chit-chat; one memorable night I came home to a dozen Irish girls, who invited me to have a drink with them and hear about their experiences of America.

For those unfamiliar with coliving, the idea of “living with strangers” can seem strange — but these interactions capture exactly the lightness that coliving offers. I could have spent more money on a private sublet and come home every night to an empty apartment. Instead, I got real moments of human contact, glimpses into lives different from my own, and a sense, as small as it was, of not being completely alone.

Bedford Avenue was always meant to be temporary, and on balance I got exactly what I needed: a decent place to live, on flexible terms, in my preferred location, at an affordable price-point. I had pleasant interactions, contributed to the apartment’s maintenance, and was able to keep my life moving forward.

Moving Out

I left the apartment after two months to transition into my long-term place in neighboring Clinton Hill. A few weeks after leaving, the reality of SettleLiving became clear. They did not want to return my deposit.

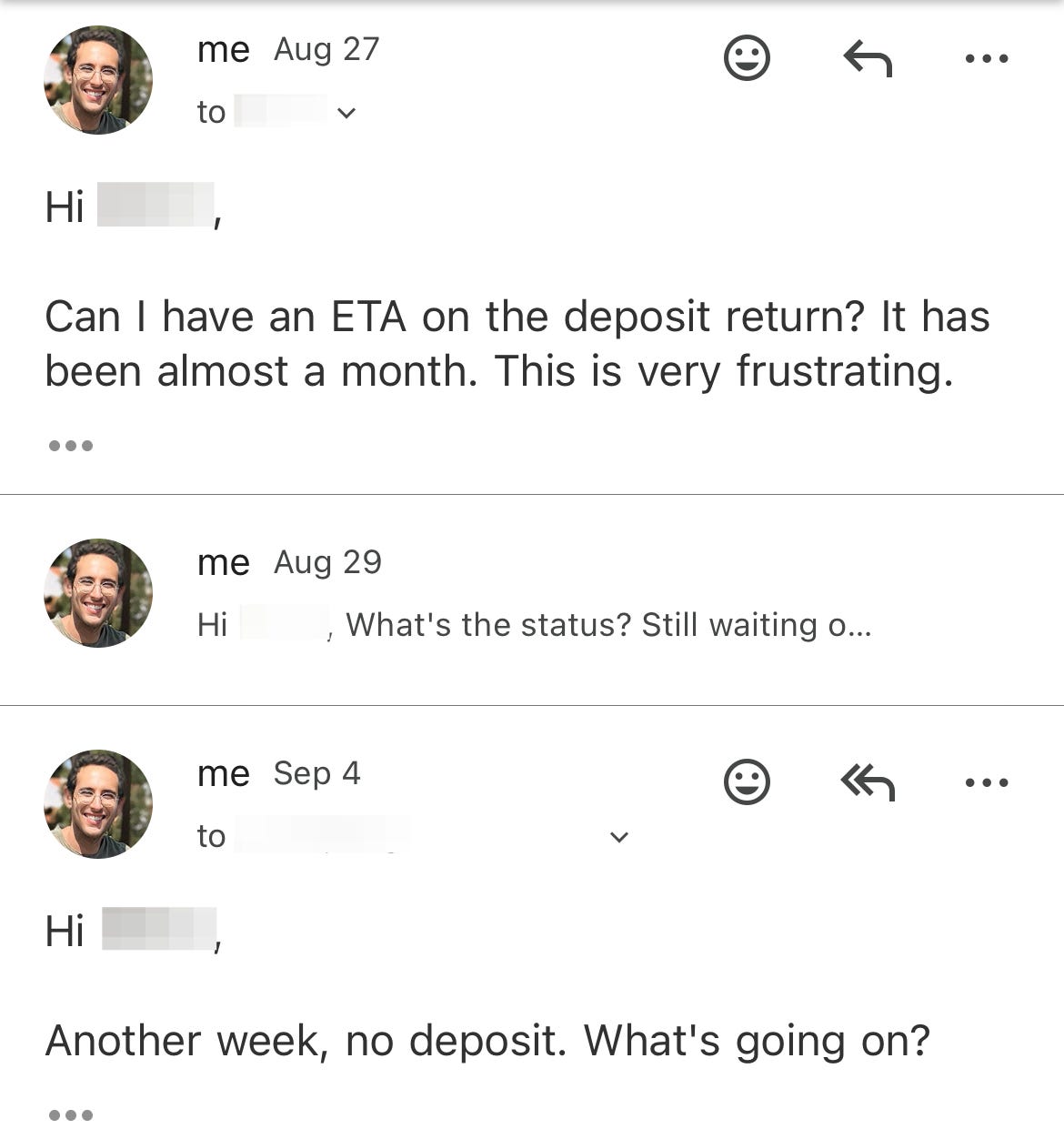

It was subtle at first — slow responses, “we’ll get back to you” texts, and so on. About a month after moving out, I started to get that sinking feeling in my stomach. While there are legal means for recovering security deposits, many of Settle’s residents are young internationals who by-and-large are not going to be able to navigate the American legal system. I began to suspect that Settle purposefully slow-walked refunds, knowing that a large proportion of their residents would eventually give up.

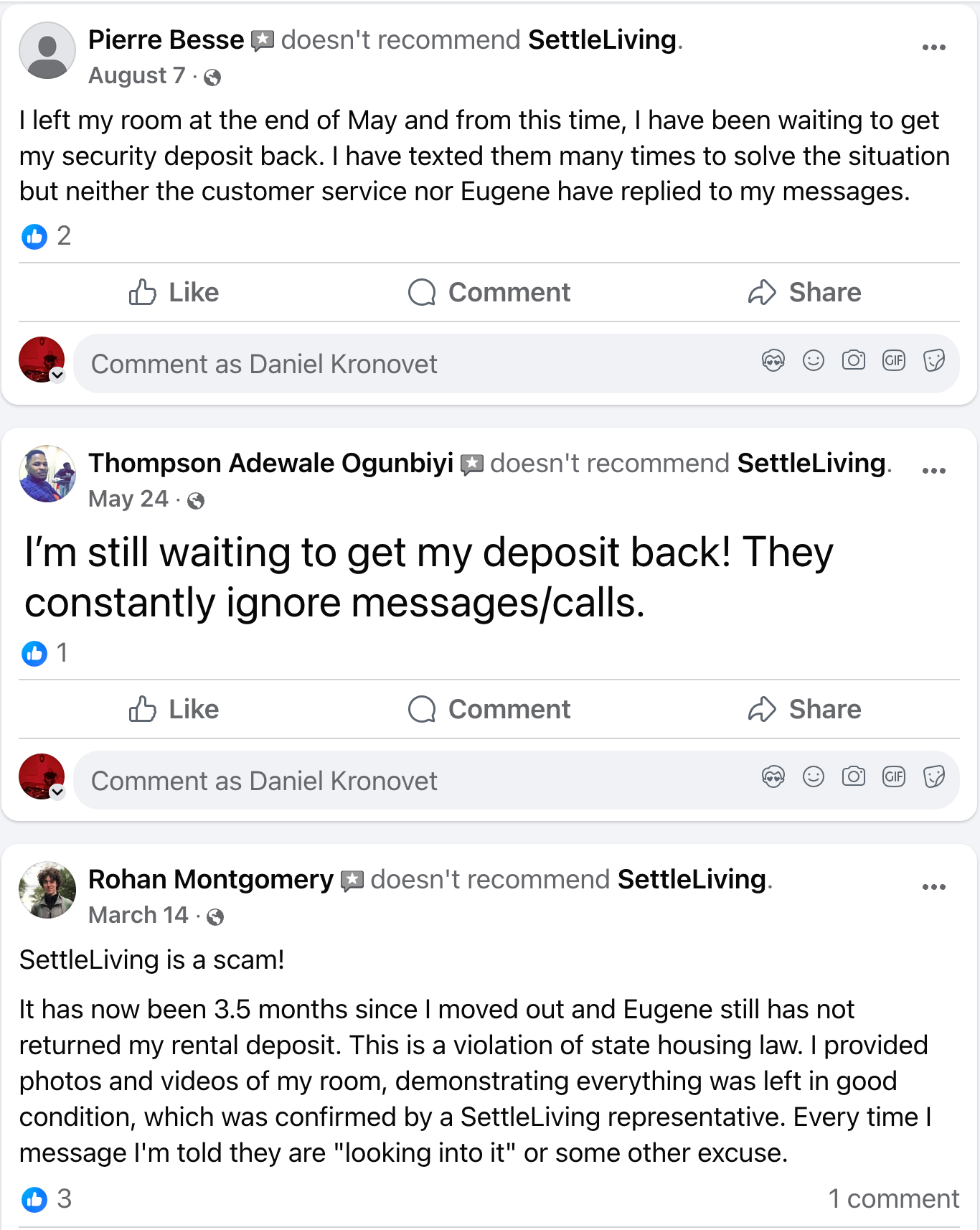

I looked up their Facebook page, where my suspicions were confirmed:

I had to open disputes with PayPal and threaten legal action before I got my deposit back, a process which took forty-two days.

I can’t say conclusively that SettleLiving is committing bad-faith withholding — their slow-walk gives them plausible deniability, and my funds were ultimately returned. But I suspect that many of their international residents never got their deposits back.

Conclusion

I moved into the Bedford Avenue apartment because I needed housing, but also because I wanted another data point about coliving broadly. How do other organizations do things? Is there some secret sauce they have that I don’t? Who exactly is the market, and what is it that they want and need?

Reflecting on the experience, I can draw two clear (and contradictory) conclusions.

The first is that there is still far too much room for abuse between landlords and tenants. That an organization like SettleLiving could acquire a portfolio of apartments with no up-front capital, sublet rooms at marked-up rates, manage them poorly, and then withhold deposits from vulnerable foreigners — without experiencing any real consequences — strikes me as deeply wrong.

Having been on both sides of the table, as both a renter and an owner, it’s clear how much distrust exists on all sides. Incentives are fundamentally mismatched: renter horizons are short-term, while owner horizons are long-term, leading to “prisoner’s dilemma” style outcomes where each party tries to avoid being the sucker to the other. Society copes through a mix of market-distorting regulations and exclusionary heuristics like “fit.” It’s a bad situation, and everyone is losing.

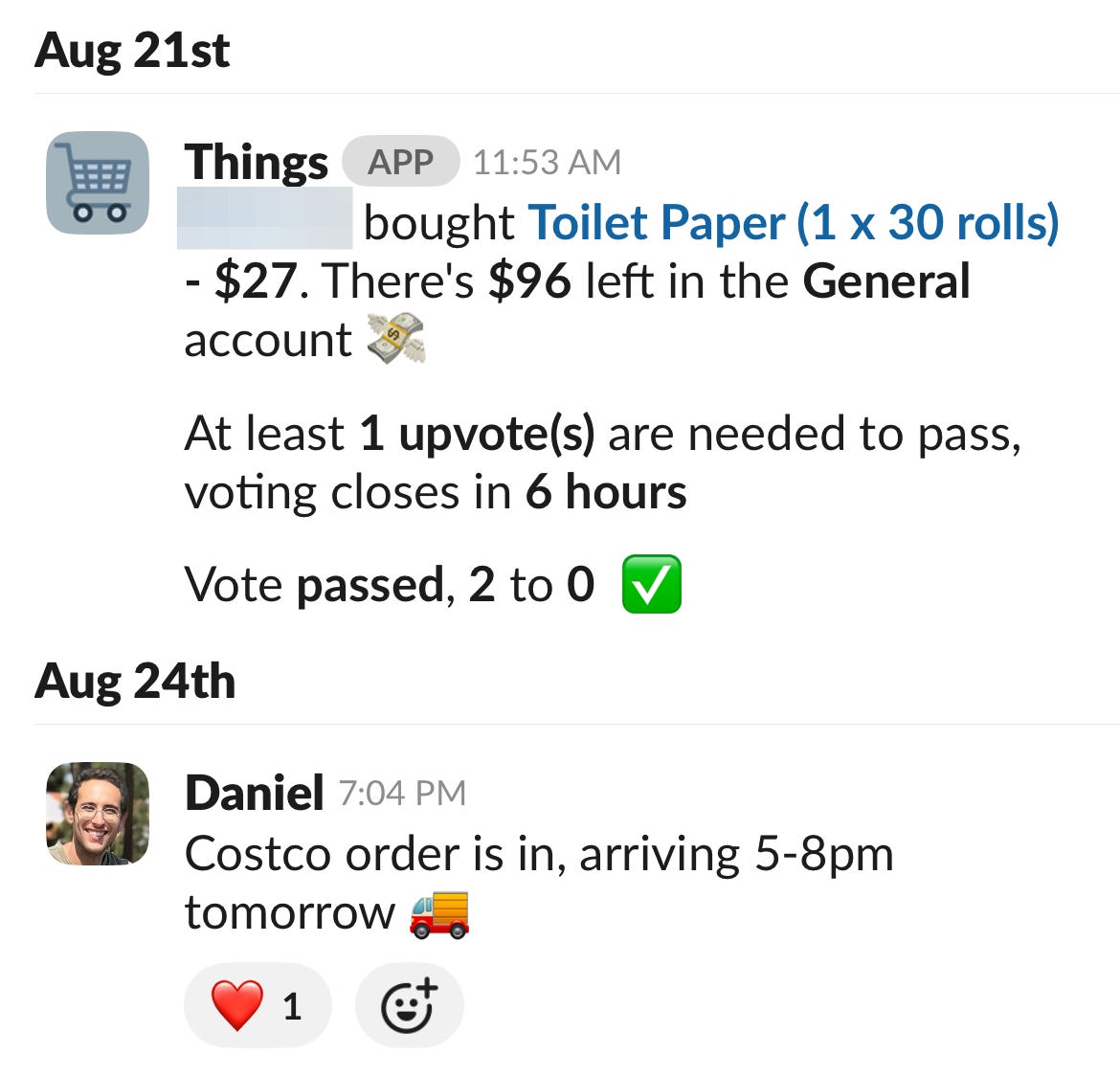

With Zaratan, we have tried to move this needle through operational innovations which better align residents and owners: a revenue-share through which operational savings are returned as rent credits, and a resident-directed food and supplies budget so that high occupancy translates into greater discretionary spending:

The second is that despite all of Settle’s shortcomings — from sloppy operations to bad-faith withholding — they filled a real need in the housing market. As a renter, being able to search for rooms based on price and location, and to have a consistent point of contact for leasing and move-in, made all the difference in a market otherwise defined by high costs and poor communication.

Coliving is an important and underserved niche, and operating it correctly requires a certain amount of specialization and sophistication. But even mediocre operations can provide value.

SettleLiving solved for access but not for trust, whereas Zaratan tries to build trust directly into operations, through process innovation and incentive alignment. To give an analogy, SettleLiving is an inefficient coal engine, belching externalities but still doing economic work; Zaratan at its best is a clean-energy alternative, doing similar work with much greater efficiency.

In the end, Settle offered shelter, but not security —

and the gap between the two is what coliving should aim to close.

Overall, my time at Settle only strengthened my conviction in both the importance of coliving as a housing model and in Zaratan’s approach to advancing that model.

It’s not that I couldn’t have afforded one of these rooms — I just didn’t want to. I have never spent more than ~12% of my income on rent, which has let me save and take on more risk.

As I have written before, I think organizations rely too much on unenforceable policy to regulate behavior. I would prefer less written policy and more peer feedback mechanisms.

woah bro, I also had a shady property manager named Eugene in Bushwick. I just didn't pay my last month's rent to make sure I got my deposit back hah. Wonder if it's the same guy....

Yeah, I've been slow walked out of deposit before, using the responsible party is in the hospital excuse. You are on the right track, and as I said, if I get any traction with Mamdani, I will bring you in.