The Tragedy of Microapartments

Coliving as a path to deep affordability

A few weeks ago I went to one of Daniel Golliher’s Maximum New York events in Williamsburg. After the presentations, I struck up a conversation with Ian, a young developer working in sustainable, mixed-use residential construction.

As I often do in these situations, I brought up my work with Zaratan. I am always curious to get the perspective of people in the industry, and to better understand how our model of naturally-affordable, lightly-managed coliving fits into a broader vision of housing development.

Ian was intrigued, and seemed genuinely impressed by Zaratan’s operational innovations. When I finished my pitch, he hit me with this:

Seems cool, but do people really want this?

Ian shared that at his firm, leadership is much more interested in microapartments (one-person units in the ~200–400 sqft range) than in coliving. Among real estate developers, these high-efficiency units are seen as a potential answer to the cost-of-living crisis, letting builders deliver housing at lower price-points while side-stepping the messy human challenges created by the relationship-centric coliving.

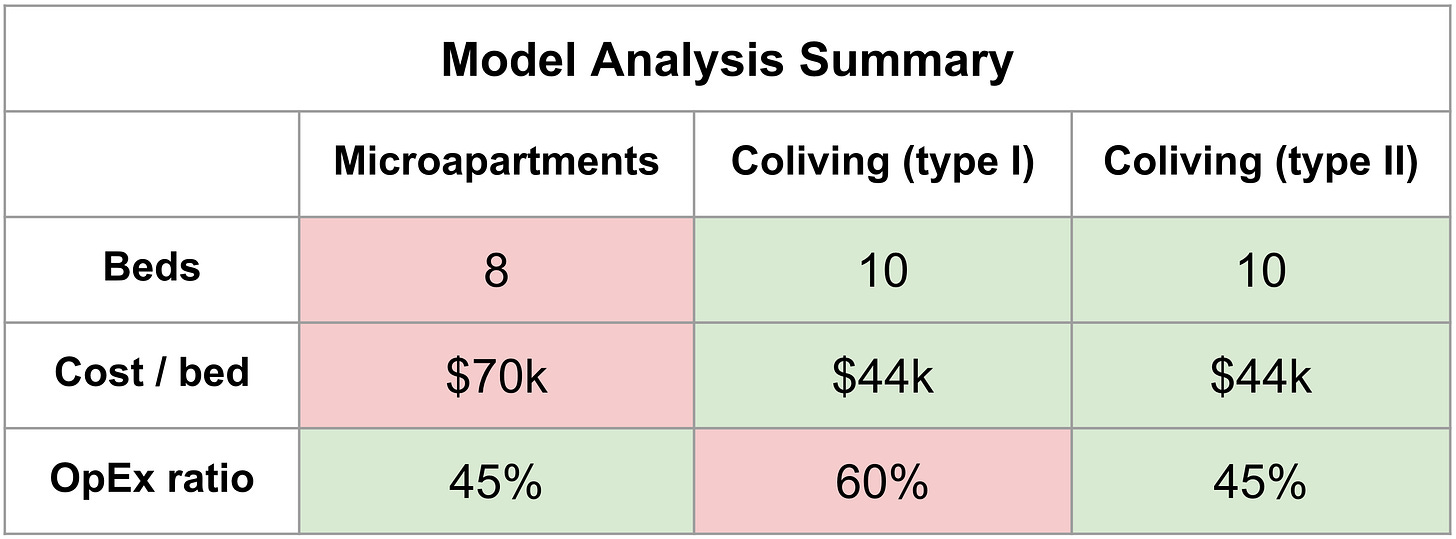

In my view, this is a tragedy: compared to coliving, microapartments cost more and deliver less. The rest of this essay will contrast microapartments and coliving along four dimensions: density, build cost, operating cost, and desirability — and make the case for coliving as the better path to housing affordability.

The Example of Carmel Place

In 2016, New York saw the opening of Carmel Place, the city’s first microapartment building. Here is a sample floor plan:

This ~300 sqft unit offers a convertible living/bed area, kitchen sans range, and 3/4 bath, with large windows and high ceilings creating a feeling of space. The units were priced on par with regular studios, with the higher cost-per-sqft justified by way of building amenities. 90% of units leased within two months of opening.

This leads us to the natural question: what could it have looked like as coliving?

Microapartments vs. Coliving

Let’s walk through a hypothetical high-density project, modeled either as microapartments or as coliving. In both cases, we take a 60x40 (2,400) floor plate as our starting point. Our goal is to create as much quality housing as affordably as possible, with quality defined broadly as “a place people don’t immediately want to leave.”

We'll evaluate the models across four dimensions:

How many rooms can we create?

How much will they cost to build?

How much will they cost to operate?

How appealing will they be to renters?

I: Space Efficiency

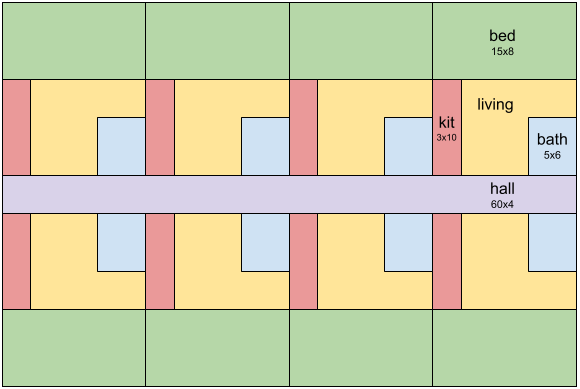

Here is our 2,400 sqft floor mocked up as 270 sqft microapartments:

Each of these units is identically laid out, with a 120 sqft bedroom, 30 sqft bathroom, and 10 ft Pullman kitchen, with the rest being generic “living” space. Bedrooms take up 40% (960 sqft) of the total space, while 10% (240 sqft) of the floor is hallway, unrentable space which generates no value.

These layouts were designed to reflect a “reasonable” living situation. A 120 sqft bedroom is a nice space — noticeably bigger than a 90 sqft “cramped-but-livable” efficiency room. A 30 sqft bathroom can accommodate a tub and does not feel “tiny.” Overall, these are meant to represent comfortable places people are willing to stay in long-term, versus churning out of at the first opportunity.

Now here is the same 2,400 sqft floor mocked up as a single large coliving space. The bedrooms and bathrooms are identically sized as in the previous example:

In this example, we have lined ten 120 sqft bedrooms along two walls, placed a single 300 sqft kitchen at the back, and added four bathrooms in the hallway, arranging everything around a large central living space. In this setup, bedrooms take up a full 50% (1,200 sqft) of the total space, while only ~8% (200 sqft) of the floor is hallway.

A few things jump out at us:

The first is that we have created two additional 120 sqft bedrooms compared to the microapartment layout. Per square foot of buildable space, we have achieved 25% greater density (10 vs. 8). This is significant.1

The second is that we have created much more common space for the residents. The 300 sqft coliving kitchen is ten times as large as the Pullman kitchens built into the microapartments. Rather than a single hot-plate and small refrigerator, the kitchen can now accommodate multiple gas ranges, fridges, appliances, and prep surfaces. Every resident gains access to better resources, raising the ceiling on what kinds of cooking becomes possible both individually and collectively.

The living space is also larger. A key part of coliving’s appeal is the promise of “luxury and abundance, at craigslist prices.” Creating a place that feels precious and has emotional resonance is what drives the community dynamic: people want to spend time at home, and with each other.2 Pure cost optimization risks creating the type of “down and out” SRO environment that people rightly avoid.

The third is that residents are sharing bathrooms. Bathrooms can be a complex and charged topic; for now we’ll say that a ratio of 3:1 people per bathroom is about the limit of “quality.” The proposed layout has a ratio of 2.5:1, comfortably below that max.

II: Development Costs

Let’s assume the following hypothetical construction costs:

$150 / sqft baseline cost (framing, electrical, drywall, etc)

+$10,000 per kitchen and bath, for plumbing and fixtures

+$5,000 per bath, for tiling and waterproofing

Real costs will vary widely, but this should be directionally correct.3

In both examples the baseline construction costs are the same: $360,000 ($150 x 2,400 sqft). In the microapartment example, an additional $80,000 ($10,000 x 8) goes to kitchens, and $120,000 ($15,000 x 8) to bathrooms, for an all-in cost of $560,000, or $70k per bed. In the coliving example, the kitchen and bath costs are lower: $20,000 goes to a single larger kitchen (doubly-programmed, so $10,000 x 2), while $60,000 ($15,000 x 4) is spent on bathrooms, for an all-in cost of $440,000, or $44k per bed. The end result is a 21% cost savings vs. microapartments — while providing 25% greater density.

Taken together, for every $100,000 of investment, we get 2.3 beds of coliving, versus only 1.4 beds of microapartments — an efficiency gain of 64%.

While this example is simplified, the dynamics are real. Thesis Driven’s Brad Hargreaves, founder of Common and long-time housing innovator, has written about the challenges of realizing cost savings through microapartments:

[The] affordability benefits of microapartments versus typical studio apartments tend to be modest until unit sizes get quite small. After all, the most expensive parts of construction—the [mechanical, electrical, and plumbing] and fixtures that come with kitchens and bathrooms—are just as costly in microapartments as they are in normal apartments.

In terms of both density and quality of housing, coliving beats microapartments hands-down.

So - what’s the catch? Why aren’t we all living in affordable coliving mansions?

It’s time to talk about operations.

III: Operational Complexity

Operational expenses — maintenance, management, taxes, and insurance — typically consume 30–40% or more of a building’s income.4 The ability to control these costs makes or breaks a housing project.

With microapartments, every unit houses one person. While the building might offer shared amenities — lounge, gym, etc — the units revolve around individuals. As such, let’s assume microapartment operational expenses are at the high end of typical, around 40–45%.

In contrast, coliving units house many people, who share kitchens, bathrooms, and living areas. This introduces complexity which, if not handled well, can devolve into low resident satisfaction, high vacancies, and foreclosure.

Among the grassroots coliving communities profiled by the excellent Supernuclear, these complexities are mostly handled through social filtering. Vacancies are shared on private networks, with roommates chosen based on existing relationships. While this does help manage complexity — roommates are pre-selected for interpersonal compatibility and shared values — it limits the viability of coliving as a general model.

Further, “lightning-in-a-bottle” approaches to community-building deter investment. A community with a 10% chance of breakdown in any given year is likely to fail within 7 years — an unappealing prospect to an investor looking to make a 30-year commitment. For coliving to be a buildable housing category, it must be able to integrate individuals across large social distances, be less dependent on heroic personal leadership, and be able to easily and reliably reconcile differences of preference and opinion.

Broadly, there are two ways to achieve this:

Coliving-as-hostel (type I)

The first and most common approach is to treat coliving as a type of hospitality, framing the coliving “experience” as a product to be sold. The property management is a high-overhead, employing staff to clean common spaces, “create community” through event programming, and resolve interpersonal conflicts. These extra costs can push rents up to or even above market, as the cost savings of density are redeployed towards services. In this model, coliving operating expenses can consume 50-60% or more of rental income — up to 1.5x more than microapartments.

This is the approach taken by organizations like Cohabs, who cater to young renters looking for hostel-esque experiences, offering 80 sqft rooms in Brooklyn for $2,000 per month.5 While this model works, it can be brittle, as high costs often lead to churn. The now-defunct Campus failed in part due to its residents forming friendships and moving out into cheaper apartments, leading to high vacancies.6

Ultimately, this approach risks falling into the vicious cycle of high costs → high rents → high churn → high costs.

Coliving-as-cooperative (type II)

The second approach is to treat the coliving house as a true cooperative, emphasizing self-governance and mutual aid.7 This approach puts a higher expectation on the residents to handle the logistics of their day-to-day, including cleaning, community building, and conflict resolution, while also allowing more of the cost savings of density to be passed on to the residents.8 Under this model, operational expenses are closer to that of traditional multifamily — around 40% of rental income.9

Traditional cooperatives often rely on parliamentary or sociocratic organizational structures (meetings and committees) to make decisions. These models work, but can be prohibitively time-consuming.10 An alternative approach, often taken by the grassroots communities mentioned earlier, is to minimize explicit structure and rely more heavily on social filtering to maintain group consensus, which limits accessibility.

A third approach, less common but potentially more effective, is to leverage contemporary systems thinking to create collaboration tools which are both simple and powerful: helping residents handle basic coordination without frequent meetings. While this might look like technology, it is fundamentally about communication. Zaratan has pursued this approach both in theory and practice — Sage House has maintained 98% occupancy for three years with minimal outside management — and believes it is the key to establishing coliving as a housing category.

In contrast to the previous approach, this one aims to achieve the virtuous cycle of low costs, low rents, and low churn.

To be clear, we do not believe that there is a single “perfect process” which can be all things to all people. There will always be a need for management, meetings, and social filtering. We do believe that it is possible to reduce the dependence on any one of these approaches, and to get better outcomes with less effort, and more consistently.

IV: Cultural Perceptions

Assuming a reliable and low-cost operating model, the unit economics of coliving become undeniable. What other barriers exist to wide-scale coliving adoption?

Ian, again:

Me, enthusiastic: part of rent goes to a shared fund, for food and supplies!

Ian, skeptical: shared purchasing? Sounds culty. What are they buying?

Me, deflated: eggs.

Coliving sits on the fringe of America’s cultural imagination. Unlike in Europe, where coliving emerges from the continent’s backpacker-hostel culture and evokes a sense of worldliness and adventure, American coliving is grounded in the West Coast counter-culture of cults, and communes. As such, the practical economic benefits of coliving are frequently obscured by these (often negative) cultural associations. If Americans do have another cultural referent for coliving, it is college dorms — managed environments for not-quite-independent young adults.11

These perceptions have consequences. Inasmuch as housing is not merely a basic necessity, but a way to signal status, this impression deters those who would otherwise benefit from coliving’s affordable rents, better housing, and opportunities for connection out of fear of social stigma.

After all, if someone could get their own place, shouldn’t they want to?

Fortunately, this problem is tractable. The benefits of coliving are so clear, and the reservations so superficial, that a compelling cultural narrative could meaningfully shift public perceptions. If our taste-makers could convince us that milk would make us strong, and that diamonds would lead to happy marriages, they can surely convince us that coliving reflects emotional maturity and financial wisdom.

Coliving doesn’t need to be for everyone. Families have different needs for private space than mobile singles, the demographic coliving best serves. But that market alone is huge — there are over 50 million people in the US aged 22–35. Assuming rent of $1,250 per month, just 10% of that population choosing coliving adds up to an annual demand of 75 billion dollars.

While cultural perceptions of coliving may be suppressing demand today, they tell us little about the potential demand for coliving tomorrow.

Conclusion

As someone who studied mathematics at the graduate level, I truly cannot imagine a straighter line than the one which runs from America’s housing-affordability and social-cohesion challenges to large scale coliving adoption.

Microapartments represent a local maximum — a decent solution to a challenging problem, but one constrained by limiting assumptions. Coliving represents a superior maximum — offering better housing at lower cost — but requires critically interrogating assumptions which often go unchallenged.

America is collapsing under the weight of increasingly unaffordable housing, rapidly deteriorating social capital, and diminished economic prospects for young people. Coliving — offering abundant, affordable housing and ample opportunities to form meaningful relationships — is an obvious solution.

We are sleeping on an enormous opportunity for both affordability and abundance, and that is a tragedy. Stop building microapartments, Ian. Build coliving.

Some jurisdictions have legacy rules around unrelated individuals living together; savvy coliving operators have developed workarounds. A full treatment of the topic is out of scope for this essay; for sake of argument, let’s assume those issues have been resolved.

My first coliving experiences were in the “hippie mansions” of Berkeley, and the impression stuck.

See this Deep Research report for more information about multifamily construction costs.

See this Deep Research report for more information about coliving operating expenses.

I once visited a Cohabs location in Prospect Heights. The residents were young and seemed happy; I doubt that most of them were paying their own rent.

Based on a conversation I had with a former Campus employee.

Rented coliving spaces are not technically “cooperatives,” as the term implies member ownership of the physical assets. In practice, residents can meaningfully “own” the community and daily operations without owning the physical space.

Some are skeptical of the idea of residents cleaning. In practice they are quite willing, as long as expectations are set correctly and the affordability benefits are clear.

Sage House operational expenses have historically come in at about 40–45%.

As Oscar Wilde said: “The trouble with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings.” As a member of the North American Phalanx said: “Our days were spent in labor, and our nights in legislation.” And this, and this.

It is noteworthy that Outpost Club, one of the more successful coliving operators in New York, partially positions itself as “student housing.”

I enjoyed this essay! You make a strong case for this as living situation that seems to have practical benefits for all involved.

What a cogent, wise and inspiring analysis. Having lived for several years in the University of Michigan co-ops, I have spent a lifetime longing for a similar set up for grown ups. Now retired and recently divorced, it seems so obvious.