The Sacred Machine

Embeddedness and orientation in socio-technology

This essay is part two of a two-part series. You can read part one here.

Last month’s essay explored the concepts of the magic circle, and the sacred and profane, linking them to the history of intentional communities — who tried to protect themselves from the dehumanizing effects of industrial capitalism by creating and inhabiting “magic circles” of sacred relationships.

The implications of these ideas are broader, however, and get at the heart of our collective effort to build a vibrant and complex society: learning how to scale complexity, while preserving the human substrate.

The Limits of Structure

One domain where these questions have attracted vigorous interest is web3 governance. Many, myself included, were drawn to web3 out of an aspirational desire to build better institutions, only to be disillusioned as we repeatedly watched web3’s ideals struggle against the realities of bad actors and hard problems.

Web3 leaders have long wrestled with this challenge. The argument roughly goes:

Game theory lets us design economic systems which encourage, if not outright guarantee, desirable behaviors and outcomes.

However, these guarantees go away if participants are able to collude outside of the system, going “around” the rules as written.

Financialized (extractive, zero-sum) outcomes occur in the absence of collusion prevention, as positions of influence can be sold to the highest bidder.1

The challenge is to create and sustain a “civil society” outside of crypto-mechanisms, where social values (e.g. fairness) can be consistently upheld.

This line of thinking echoes Karl Polanyi’s landmark argument in The Great Transformation: industrial capitalist society marked the shift from a world where markets were embedded in social life — a small part of a larger whole — to one where society itself became subject to market logic. Structures and systems allow greater complexity, and thus greater abundance, but the replacement of relationships with transactions creates opportunities for exploitation and abuse.

In his 2021 essay on the limits of cryptoeconomics,2 Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin concludes that “financialized systems are much more stable if their incentives are anchored around a system that is ultimately non-financial.” The task before this generation of institutional builders is to articulate a design framework for repeatably weaving together transactional (short-term) and relational (long-term) systems into deeper and richer new wholes — thereby capturing the benefits of structure, such as greater freedom and robustness to discrimination and bias, without losing the psychological benefits of meaningful relationships.

Engineering the Sacred

A question that has long interested me is how technical systems can be embedded into social contexts in a way that supports, rather than undermines, the social body — much as the skeletal system both supports and is supported by the body’s soft tissues.

Over the last several years, I was fortunate to work on two projects — Colony and Zaratan — which attempted to put these ideas into practice. The rest of this essay will draw case studies from these projects, and synthesize design principles of embeddedness and orientation for building socio-technical systems.

Mechanism design is often framed as a discipline under economics and game theory. We might be better off treating it as anthropology, with culture and values as first-class citizens. Let’s explore what that looks like in practice.

Colony’s reputation system

For six years I was a core contributor to Colony, a pioneering web3 DAO platform (“ants, not empires”), developing mechanisms for helping distributed teams more effectively work together. One of Colony’s primary innovations was a contextual reputation system in which reputation was 1) earned by doing work, 2) could not be sold or transferred, and 3) decayed automatically over time. Unlike the fully financialized token-governance schemes then (and still) prevalent in web3, Colony’s system incorporated aspects of what we might consider “the sacred” — in which decay reflects an underlying sacred time, rather than being the result of unoriented human action.

Earning contextual reputation through peer-reviewed labor embeds the score in a relational network (the “magic circle” in this case being the intra-firm arena). The loss of reputation over time makes the number meaningful and keeps the global reputation distribution dynamic.3 Inasmuch as these mechanistic elements map analogously to real-world reputation dynamics — hard-earned, relational, recency-biased — this design lets emotional resonance to accrue to reputation in a way that it simply cannot to a fully financialized token, whose directionless fungibility precludes the emergence of a relational play-space.

Colony’s reputation system was first presented in late 2017, in the middle of the ICO boom, and was both prescient and remains relevant to this day.

Colony’s reputation system

Peer evaluation & non-transferability (embeddedness) + continuous decay (orientation)

Chore Wheel’s “Hearts” system

In early 2020 I founded Zaratan Coliving to tackle the housing affordability crisis, and have been working to establish it as an innovative voice in its various ecosystems. Recently, the bulk of that effort has gone into Chore Wheel, our open-source suite of community governance tools, and a key part of what has allowed Sage House to sustain high occupancy and low rents for almost three years.

Early in the project, a lot of thought was put into how different pieces of information would be made explicit (represented symbolically), or left implicit and thus dependent on an evolving intersubjective understanding. Our intuition was that the more that could be left implicit, the more easily the formal system could be grounded in a relational context. The challenge was introducing just enough structure to be load-bearing, without inadvertently displacing — and ideally meaningfully integrating — the human substance.

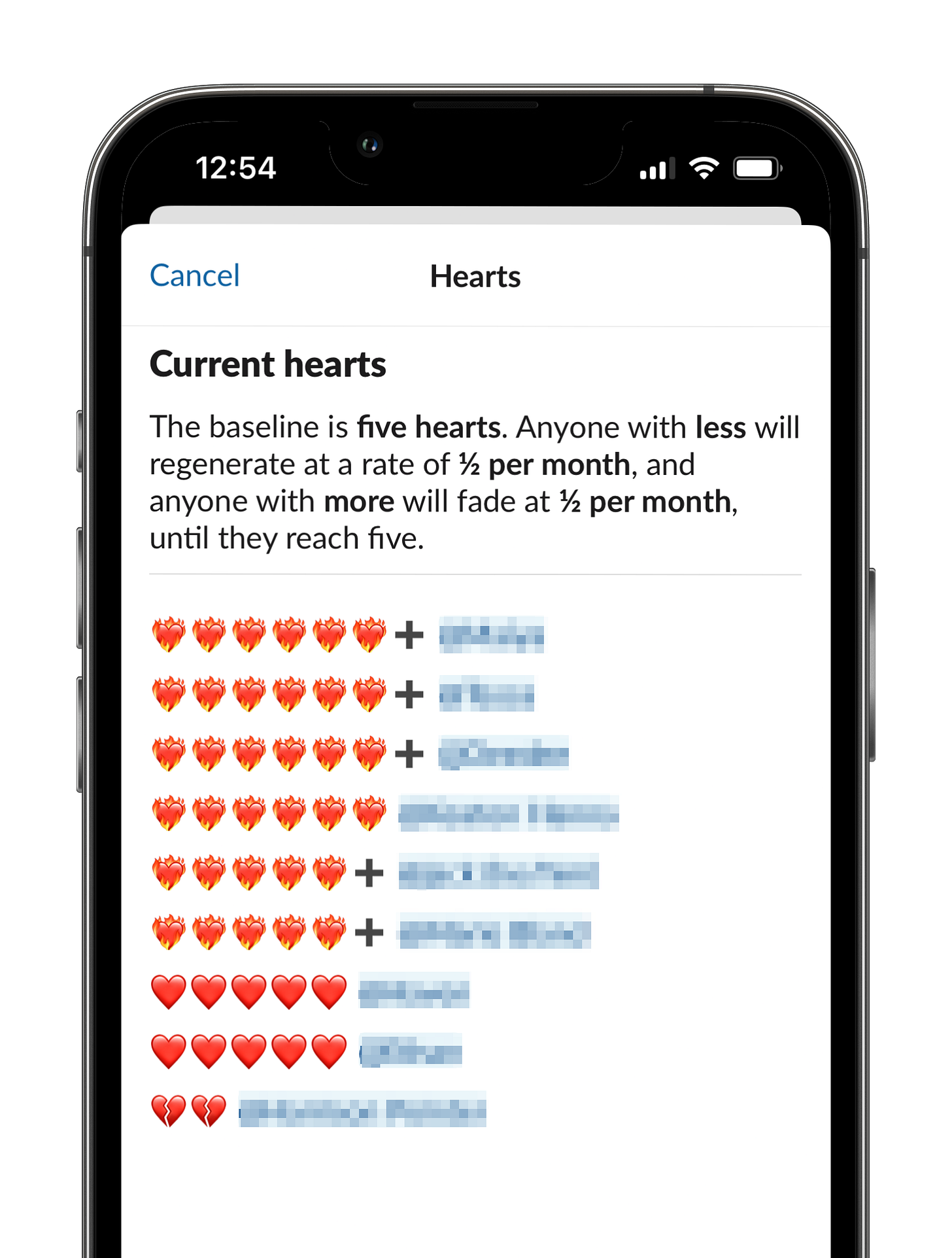

The Hearts system is an example of this dual-layered design. All residents begin with 5 hearts, earn hearts by doing chores and receiving karma, and lose hearts for shirking chores or violating group norms. Every month, residents with more than five hearts “fade” ¼ hearts, while residents with less than 5 “regenerate” the same. A resident with many hearts gains special affordances, such as a lower approval threshold for purchases, while a resident who loses all their hearts pays a resident-determined fine, operationalizing Elinor Ostrom’s principle of graduated sanctions.4

While the number of hearts a resident has is explicit, the conditions for gaining and losing hearts are embedded (in multiple ways). As a chores accountability structure, hearts are derived from peer assessment of objective contributions; as a norm-setting tool, hearts emerge more fluidly from evolving culture and values. The homeostatic return-to-baseline orients the mechanism around forgiveness over time, allowing hearts to support meaningful emotional repair. By combining computational bookkeeping with human judgment, we expand the relational play-space without subjecting participants to a cold, transactional logic.

Chore Wheel’s “Hearts” system

Peer evaluation (embeddedness) + gradual return-to-baseline (orientation)

Chore Wheel’s “Chores” system

If Hearts provides a long-term accountability system, the Chores system helps coordinate daily regenerative tasks. Instead of an inflexible chore schedule, unreliable bragging board, expensive cleaning staff, or invisibly-laboring chores cop, residents do chores for points. The value of a chore rises with neglect, and residents can steer points towards higher-priority tasks, mixing individual contribution with collective determination. At the end of the month, points reset to zero, preventing compounding accumulation (or debt).

When developing the system, we initially tried to link points to rent, with the idea being that residents could do extra chores for lower rents. Imagine: an aspiring artist, in lieu of a second barista job, could contribute more around the house, while a busier professional could “buy back their time” in exchange for higher rent, all organically and dynamically. From a rational-actor perspective, it seemed like a great concept.

In the end we dropped the idea, for both legal and social reasons, and in retrospect I’m glad we did. While nice in theory, the points-for-rent would have undermined the “magic circle” of communal life by introducing external wealth disparities into an otherwise relational space. Chore points would have ceased to be a community currency representing mutual care, but simply have been “dollars with extra steps” — embedding the house in the larger economic market, instead of creating a miniature “chores market” embedded in the social relationships of the residents.

By keeping points socially embedded, we created a system to structure and motivate a vigorous process of culture-building, where residents engage in focused discussions about how to best leverage these mechanistic affordances to better live together.5

Chore Wheel’s “Chores” system

Peer evaluation & prioritization (embeddedness) + shared monthly cadence (orientation)

Design Principles

From these examples, we synthesize two design principles for socio-technical systems: that of embeddedness and orientation.

Embeddedness

Embeddedness is the idea that a system should be responsive to human thoughts, feelings, and values, instead of imposing machine values onto people.

Colony, Hearts, and Chores all rely on human review—Polanyi’s “embedded markets” in miniature—to keep reputation, hearts, and points grounded in real relationships. Instead of, for instance, mounting a camera over the sink and using computer vision to decide if the dishes were done (a real suggestion I received), or running a large-language model over a work product to produce an automated assessment of quality, participants verify each other’s claims.6 While arguably “inefficient,” the reliance on peer judgment keeps the explicit symbols (reputation, hearts, points) grounded in a mutual intersubjectivity, instead of being imposed exogenously by a (potentially misaligned) technical system.

As neural networks continue to mature, and practitioners in every industry are exploring ways to leverage these tools to augment and automate manual processes, the question of where to automate, and where to embed, decision processes will become increasingly critical. Leaders like Audrey Tang and organizations like the Collective Intelligent Project are doing key work in this area.

Orientation

Orientation is the idea that the system should be built with an innate sense of direction and momentum, defined as much by what it can’t do as by what it can.

This idea connects to our discussion of the sacred. The sacred is a fixed point — the pillar of the temple, the hour of the festival — around which experience revolves, while the profane, uniform and relative, drifts without orientation. The sacred precedes and defines us; the profane follows and is defined by us.

In our examples, meaning and relationality are preserved through an orientation, an asymmetric limitation on what a symbol can do. A fungible token has no orientation — it can be sent up or down, left or right, forward or back. This homogeneity means a token can accrue no meaning or history, apart from financial value.

Contrast this with Colony’s decaying reputation, or the idea of a non-transferrable “soulbound” token: their deliberate, asymmetric restrictions allow these symbols to acquire both meaning and history, enabling a deeper relationality

Conclusion

Here is a screenshottable (wink) summary of these concepts:

Designing Sacred Machinery

Principles

Embeddedness

Ground assertions in intersubjectivity, avoid gameable sensors

Orientation

Fundamental asymmetries encourage meaning and memory

Provocations

Homeostasis over hoarding

Ephemerality deters whales and preserves dynamism

Protect the circle

Keep the profane (money) out of sacred (relational) spaces

Create culture through ambiguity

If possible, under-specify rules and let culture fill the gap

The major trend in crypto-economics today is to acknowledge the limits of economic incentives, but to nonetheless try to compensate with even more explicit structure.

Perhaps the better answer is to strategically under-mechanize, and instead deploy principles of embeddedness and orientation to design socio-technical systems where norms, values, ritual, and culture emerge organically as first-class citizens. This lets us build systems as complex as we need, without losing the humanity we built them for.

A classic example is the “51% attack.” I borrow to buy 51% of a company’s stock, then vote to give myself 100% of the company’s assets — enriching myself and ruining the company.

A response to Nathan Schneider’s “Cryptoeconomics as a Limitation on Governance”.

During the project’s development, the choice was made to let colonies “slash” reputation in cases of bad behavior. Exploring whether this new affordance expanded the range of use-cases, or undermined the semantics of reputation, is left as an exercise for the reader.

To mitigate potential clique abuse, heart loss due to norm violation has an adaptive upvote threshold: 40% of residents must approve a minor violation, 70% a major violation. When issuing a fine, all residents individually decide a fine (up to a maximum), and the penalty is the largest of those fines. The effect is that the most aggrieved resident sets the penalty.

Sage residents would like me to clarify that the Chores app is far from perfect and that they still spend a lot of time talking about expectations, but overall they’d still rather keep the system and in general are fairly happy.

An open question is what kinds of user experiences will make this type of continuous feedback-gathering both effective and engaging — a topic I’ve written about elsewhere.

I appreciated your sentiment, your work, and the ongoing formalization of your thoughts. I’d love to see your projects evolve and flourish.

Responses to direct quotations:

“Financialized (extractive, zero-sum) outcomes occur in the absence of collusion prevention"

1. It’s not evident to me that financialization is equivalent to zero-sum. 2. It’s not evident to me that extraction is necessarily undesirable; e.g. we extract calories from plants when we eat them, and this is desirable to me.

“Structures and systems allow greater complexity, and thus greater abundance, but the replacement of relationships with transactions creates opportunities for exploitation and abuse.”

1. Exploitation, as a Marxian economic category, is not strictly a form of abuse/harm, but is often conflated with one.

2. Abuse happened before the “replacement of relationships with [financial] transactions”.

3. I argue that all relationships are transactions, and that the evolution into capitalism is a manifestation of more explicit and precisely calculated transactions within a larger, more complex system of transactions. There's also further evolution needed&wanted.

4. It’s not obvious to me that this transition creates more abuse than previous social forms, at least per capita (population growth would create more total abuse even with a declining rate of abuse).

“Financialized systems are much more stable if their incentives are anchored around a system that is ultimately non-financial.” The task... is to articulate a design framework for repeatably weaving together transactional (short-term) and relational (long-term) systems into deeper and richer new wholes… without losing... meaningful relationships.”

- Financial systems (as all systems) are anchored in every non-financial system which underlies them as causes, all the way to the most basic/ubiquitous causal system we can identify. I make an argument that all specific, empirical systems are anchored in a more unitary, fundamental, universal system, which we can call the ground of reality, universal law, or just the underlying incentives, which are identical to the basic facets of experience; panexperientialism.

“1) earned by doing work, 2) could not be sold or transferred, and 3) decayed automatically over time. Unlike the fully financialized token-governance schemes then (and still) prevalent in web3... decay reflects an underlying sacred time, rather than being the result of unoriented action.”

1. I think past work/experience is also valuable. This reminds me of the principle of liquid democracy, a method to calculate embedded social trust and thereby the relative reliability of various decision-makings (1. The reliability of decision makers in certain spheres, and 2 . the reliability of decisions themselves via a direct-democracy mechanism overlaid on top of a liquid-democracy; e.g. “I trust person X to make decisions about this kind of thing, but not to make decisions about who is trustworthy”, where person X then provides their perspective/policy stance as well as their trust of others in various areas, and these trust relationships are aggregated). Past experience (existing social trust) would also make global rep distribution dynamic without artificial decay / social-value deflation. Recency bias can be factored in through updated valuation systems of the experience/work itself. I think we can all agree and find instances where financialization values some work disproportionately to what we could assign as its true value, but I would not call it directionless, but rather “less intentional/long-term/deeply aware” etc. Because, it's all relative (relational). It’s also clear that financialization does emerge a relational play-space quite a lot: e.g. entertainment industries, betting, personal favors, status based social cliques, special-identity indicators (clothes, tattoos, fandom merch, makeup, art), etc.

2. I don’t follow how decay prevents lack of orientation, and I would argue that all action is oriented, fundamentally and towards the same universal objective. Otherwise, you have to invoke unexplainability/ true randomness/ “something from nothing”.

“Thought was put into how different pieces of information would be made explicit (represented symbolically), or left implicit and thus dependent on an evolving intersubjective understanding. Our intuition was that the more that could be left implicit, the more easily the formal system could be grounded in a relational context.”

- I would relate to this almost conversely. Explicit information can (and always does) evolve through intersubjective understanding. Like science. And this evolutionary tendency, and the special desire/ high valuation of it, can also be made explicit. I imagine that this enhances the rate of evolution of understanding and efficacy of systems. To be explicit about more variable or less valuable/fundamental systems could seemingly enable them to shift more easily. Everything is relatively explicit/implicit: there are degrees of precision/fullness of articulation. The more something is articulated/communicated, the more widely and deeply it is understood. I strive for understanding and explicitness in pursuit of success/efficacy.

“The homeostatic return-to-baseline orients the mechanism around forgiveness over time, allowing hearts to support meaningful emotional repair… [avoiding] cold, transactional logic.”

1. I would suggest that forgiveness does not imply forgetting past behavior, but rather the acknowledgement that change is possible, and that past challenging behavior is not bad per se, just less aligned than positive behavior – avoiding some of the shame associated with it.

2. Repair seems more likely to succeed when past behavior is acknowledged, made explicit, and when a better path forward is explicitly communicated and agreed upon.

3. Transactional logic can seem cold when the transactions are limited to those regarding money/financial markets, which are obviously limited in scope and evaluation capability. I make the case that all relationships are transactions: all relationships are intentional, cyclical flows of energy. All actions aim towards “better”, and include feedback/bidirectional flow to gauge the relative value/desirability of the outcome. All relationships have value. All action includes bidirectional subjective evaluation, and choice with regards to the evaluation of outcome (the desire/striving for better).

“Points reset to zero, preventing compounding accumulation (or debt)”

- Not sure how your systems would allow for compound growth regardless. I would suggest that long-term accounting and visibility can be helpful. Debt can be addressed in creative ways, and carries info relevant to incentivisation and expectation.

“While nice in theory, the points-for-rent would have undermined the “magic circle” of communal life by introducing external wealth disparities into an otherwise relational space.”

- External relationships always inform internal relationships: they are not and should not be isolated in understanding or in practice (which are ultimately unitary). A fear of money can be overcome by overlaying a more intentional/deeper agreement of shared value, and relating to the distribution and use of money accordingly.

“Embeddedness is the idea that a system should be responsive to human thoughts, feelings, and values, instead of imposing machine values onto people.”

- Machines were created by humans, and imposed with human values in their relationships to the social system. I have also had intense resistance to this, and capitalism, though.

“This idea connects to our discussion of the sacred. The sacred is a fixed point... around which experience revolves, while the profane, uniform and relative, drifts without orientation.”

- I agree that the sacred is more fixed. In fact, it's so fixed – so consistent, ubiquitous, and universal – that it cannot be escaped. There is no absolute profane, only that which is less or more sacred.

“In our examples, meaning and relationality are preserved through an asymmetric limitation on what a symbol can do. A fungible token has no orientation... [its] homogeneity... can accrue no meaning or history, apart from financial value.”

- Aren't limitations always asymmetric? And, isn't money limited? I have realized that all symbols, representations, references, tokens, etc. have history, meaning, and value apart from strictly capitalist relations. I think we can agree that systems beyond/outside of capitalism (emotions, biology, physics, etc.) influence our relationship with money, the way we use money, and therefore how money operates. All values are related to others.

P.s. 'Positive Realizations: One-Pagers', my most recent Substack contribution, gives an intro to my philosophical thought.