Coliving's Political Economy

Models for creating and sustaining coliving organizations

Beginning with Robert Putnam’s landmark 1995 essay “Bowling Alone,” Americans have become increasingly aware of the costs — emotional, physical, and political — of social isolation. This awareness has resulted in a growing interest in the fostering of social life, with experiments in community growing especially prominent in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

Nowhere are these experiments more compelling than in the domain of housing. By living in close contact with others, whether as neighbors or housemates, people have opportunities for the repeated casual contact which forms the basis for deeper connection. While many of these experiments are informal and small in scope, there have been attempts to institutionalize these patterns into “professional” organizations, both non-profit and for. Institutionalizing communal living offers the promise of making the benefits of this model — lower housing costs and higher quality of life — accessible to millions.

Unfortunately, many of these attempts have failed, leaving behind an “elephant’s graveyard” of disappointment. From Campus, Ollie, and Starcity to OpenDoor, Quarters, HubHaus, and Common, for-profit coliving organizations have struggled to escape the doom spiral of narrow margins and high operational complexity.

This essay will explore the “political economy” of coliving — the interactions of people, power, and capital — to help understand why professional coliving remains a challenging proposition, and what might be done about it going forward.

Shared Housing Models

Shared housing models can be broadly placed into three categories: cooperatives, grassroots coliving, and professional coliving, the last of which can be further divided into managed and collaborative approaches.

These approaches vary along two key axes: first, whether the physical spaces are owned by residents or by “capital” — a landlord — and second, whether daily life is organized primarily by residents or by outside management. As we will see, these choices have major implications for how the environment is likely to behave.

Cooperative

A housing cooperative is housing that is owned and operated by its members, who make decisions democratically. “Cooperative” is a technical term and only organizations adhering to certain rules can legally refer to themselves as cooperatives. This definition includes compliance with the “Rochdale Principles,” a set of seven democratic principles developed in Rochdale, England in 1844.1

Cooperatives are incredible organizations. Much of my early career was influenced by my time on the boards of the Berkeley Student Cooperative (BSC) and the North American Students of Cooperation (NASCO), as well as through my encounters with worker cooperatives throughout the Bay Area. I met Seth Frey, one of my collaborators in designing Chore Wheel, through NASCO, and Arizmendi co-founder Tim Huet’s “Cooperative Manifesto” remains a major inspiration for me.

Housing cooperatives have high start-up costs, including raising capital, buying assets, and establishing elaborate democratic governance processes. But for groups willing and able to put in the work, the results, in terms of building life-long relationships and securing permanently affordable, high-quality housing, are compelling.

Grassroots Coliving

In contrast to housing cooperatives, where ownership and occupancy are tightly linked, coliving models allow for a separation of ownership and occupancy.

While the focus of this essay is on organizations attempting to turn coliving into sustainable, professional businesses, there are myriad groups across the country engaging in grassroots experiments with communal housing. Organizations like The Embassy, District Commons, and The Neighborhood in the Bay Area, Fractal in NYC, both develop coliving houses and serve as hubs for sharing knowledge and best practices among those looking to “live near friends.”

The term “grassroots” does not imply a lack of professionalism, but rather a lack of centralization. These groups are sophisticated and regularly experiment with approaches to making communal living more accessible, enjoyable, and sustainable. Supernuclear, written by Phil Levin and Gillian Morris, is a great entry point into this world:

Grassroots coliving initiatives share two major characteristics: residents typically lease an entire space as a group, and expect to play active roles in establishing and maintaining their housing. The obligations placed on participants, in terms of time, effort, and risk, can be high, along with expectations for co-creation and participation in a shared culture and values.

As with the formal housing cooperatives, this style of communal life can be deeply fulfilling, but also similarly prohibitive in terms of the time and effort needed to sustain it. In addition, their relatively informal and ad-hoc nature means that they remain niche in the context of the larger housing market, often accessible only to those already within these social networks.

In simple, albeit reductive terms, we could say that with grassroots coliving, the community comes before the space; the space exists to fulfill the community.

Managed Coliving

Professional coliving-as-a-business begins with a different assumption: that for better or for worse, the population of people willing and able to create and sustain the infrastructure for communal housing, and the population of people willing and able to live in it, are different. By assuming the risk and complexity of creating and operating housing, and by renting rooms individually, entrepreneurs can “normalize” coliving: making the benefits of shared living accessible to a broader audience, while unlocking new housing stock through higher density.

To continue our reductive analogy, we can say that with professional coliving, the space comes before the community; the community exists to fulfill the space. In a sense, professional coliving is less like a tribe and more like a state, with the problem of socially integrating a disparate group coming increasingly to the fore.

Fundamentally, the business opportunity stems from the ability to realize a rental premium, on a square foot basis, through higher density. The business risk stems from the additional operational complexity caused by that higher density. Professional coliving organizations fail when the cost of managing that complexity exceeds the rental premium realized by the density.

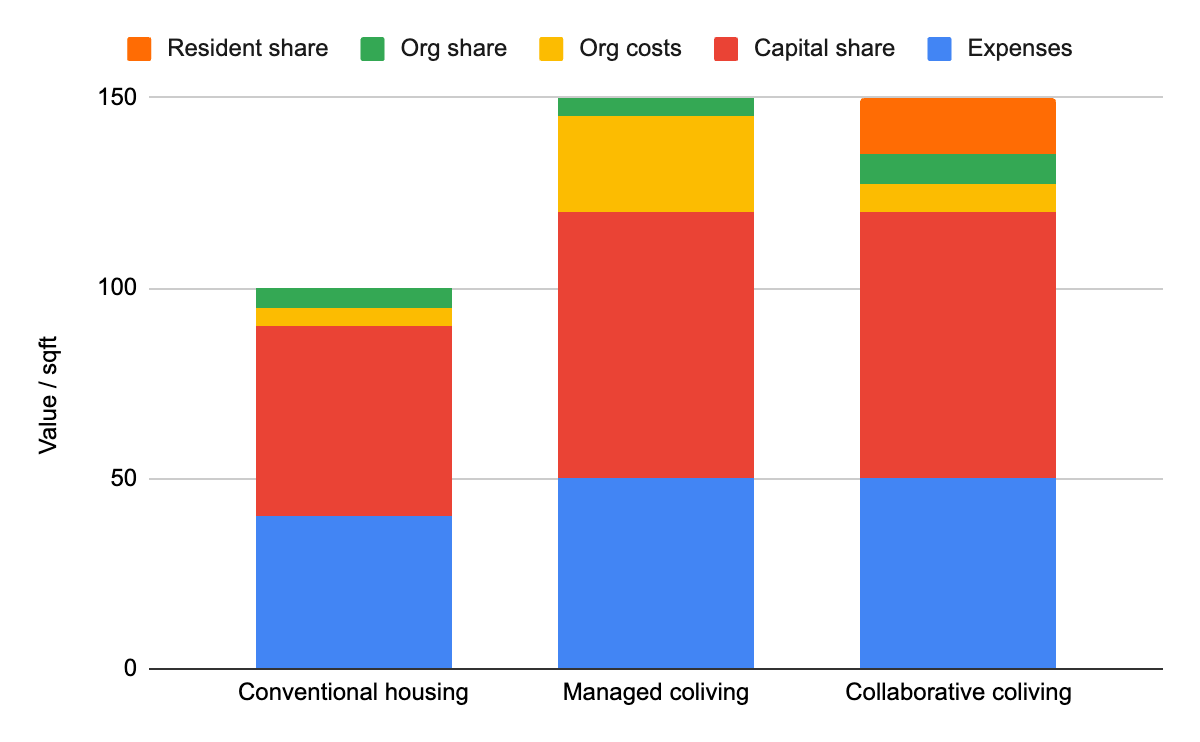

In the idealized chart below, we demonstrate how the density achieved by coliving can increase the amount of “value” (broadly defined) realized per square foot. However, while some of that surplus accrues to capital, higher operational complexity limit the surplus accruing to the management organization.

The central challenge to professional coliving emerges directly from its ostensible advantage: namely, by being relatively more accessible, participants are relatively less invested in the long-term health and success of the community. The relatively transactional nature of the relationship between residents individually, and between residents collectively and management, increases operational risk. Lacking the pre-existing social ties characteristic of grassroots coliving, interpersonal conflicts in professional coliving settings are externalized onto the organization in the form of vacancy losses and high operational expenses.

Professional coliving operators often assume these dynamics are a given. Across the board, coliving operators charge management fees far above industry standards,2 and levy hefty “membership fees” on top of base rents.3 The result is that managed coliving rooms can run significantly above market; as a consequence, operators often present coliving as a premium option justifying a higher price-tag, emphasizing convenient, shorter-term leases or novel social experiences. These economics ultimately limit the model’s impact on the broader housing market: a niche option, not a general solution.4

Ironically, these high fees are often not high enough. When presenting coliving as “community as a service,” it becomes nearly impossible to manage and fulfill resident expectations of housing quality and social cohesion. Both Common (now defunct) and Bungalow (still active) have come under fire in recent years for problematic business practices, including unresponsive management, poor maintenance and lax tenant screening. Managing interpersonal dynamics can be prohibitively expensive: OpenDoor, operating in the Pacific Northwest, went under in part due to the spiraling costs of resident mediation services.

To be fair to these operators, this is largely not their fault: structural relationships have set them up for failure. When “managed” coliving operators present community as a commodity, they create expectations which are impossible to fulfill. No rent premium can truly support the relational work that these companies implicitly promise to perform. When these companies succeed, it is through good management and a fortunate mix of residents; they remain sensitive to fluctuations in both.

Collaborative Coliving

There is an alternative. In The Art of Coliving, Gui Perdrix describes a niche of coliving operators who experiment with using technology to meaningfully integrate residents into daily operations. Done successfully (see chart below), the higher operational complexity created by density can be internalized to the residents, reducing organizational costs and leaving a surplus which can accrue to residents in the form of lower rents, better amenities, or both. As a consequence, successful collaborative models can outperform managed models in terms of both price and quality.

Sage House, Zaratan’s first coliving house, is an example of this model, operating for 2+ years at 98% occupancy, with management costs more in line with low-touch conventional housing than high-touch managed coliving.

laborative coliving is appealing in theory. However, the model can be challenging to put into practice: it is not as straightforward as simply “putting housemates in charge.” Brad Hargreaves, founder and former CEO of Common, discusses the failure of Campus to pursue just such a strategy (emphasis added):

About a week after we closed our first round of financing for Common, Campus abruptly shuttered and filed for bankruptcy protection. While this came as a surprise to many, the early Common team wasn’t shocked: we had watched them struggle with vacancy, operations, and other problems. And many of their problems could be traced back to the amount of decision-making power and control they had given their residents.

…

But from a business standpoint, handing control of their leasing process to existing residents spelled Campus’s doom. Even if those residents were fully aligned with Campus’s goals—and they weren’t—it’s unreasonable to expect that a group of busy individuals with full-time jobs and lives could effectively conduct their own tenant vetting and selection process. (Not to mention the fair housing concerns.) And as the master lessee of most of its buildings, Campus’s financials suffered as resident communities dithered over approving new members.

Successfully practicing collaborative coliving requires managing complex sets of cultural and institutional trade-offs. There are many ways one could approach these problems. In the next section, we will explore Zaratan’s approach to putting this model into practice.

Practicing Collaboration

Synthesizing the dialectic of capitalism and community is Zaratan’s animating purpose. Our project from the beginning has been to develop and refine a functional and replicable model of organization, collaborative coliving, through which light-touch management supports a resilient, autonomous community of residents.

Successfully practicing collaborative coliving requires thoughtful leadership and fundamental innovations in organizational process. We developed and refined a number of practices during Sage’s first few years, as we navigated the occasionally-bumpy process of creating and sustaining a coliving community.

These practices can be bundled into two categories: those facilitating decision-making among residents, and those supporting positive-sum interactions between Zaratan and the residents.

Handling Internal Governance

Unlike grassroots coliving, where residents typically have pre-existing ties, professional coliving must continually integrate those who were not previously known to each other. Achieving this requires practices which can flexibly handle a wide range of issues, while being simple enough for a new person to pick up quickly.

Legacy organizing patterns like meetings and committees are not the answer. As Oscar Wilde allegedly quipped, “The trouble with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings.” In the course of his intentional community research, Brad Hargreaves makes the following observation:

While residents would fiercely defend their communities, they didn’t always seem to be happy with their role in them. From interviews with intentional community participants, it became clear that a lot of their time was taken up by various decision-making processes, internal politics, and committees. Infighting abounded, and it felt like the more intentional the community, the more participants’ time and emotional energy was dedicated to petty grievances.

We built Chore Wheel to help solve to this problem, taking the latest thinking in digital governance and applying it to the specific domain of coliving houses. Avoiding general-purpose solutions and focusing instead on specific solutions to specific problems, we created systems that were both intuitive and effective.

Chore Wheel currently consists of three tools, all plugging into a shared Slack workspace. Broadly, the goal of each tool is to achieve a “Pareto effect” in its domain, solving the most common 80% of problems with only 20% of the effort.

Chores

Chores is the most sophisticated of the tools, making it easy for residents to coordinate chores. While it is easy to dismiss the idea of “residents doing chores” as naïve, in practice it brings tremendous benefit.

Cleaning is often depicted as an amenity that is “basically free.” This depiction belies the implicit assumption that domestic labor has a very low price. In reality, cleaning is expensive, and if it were priced fairly, it would be even more so.

Chores also act as a basis for social ties. In a managed coliving setting, people can isolate in their rooms, or become dependent on a “community manager” to coordinate events. Here, residents communicate and cooperate, are seen contributing, and are held mutually accountable to their commitments.

Internalizing the complexity of cleaning to the housemates not only lets them more directly shape their culture, but significantly reduces operational cost and complexity.

Hearts

Hearts is a system for mutual accountability that helps structure recognition and disagreement between housemates. Inspired by the organizational designs of Frédéric Laloux, Hearts makes it easier for untrained individuals to access best practices for conflict resolution.

By enabling residents to more easily reward contributions and resolve conflict, the potentially high cost of interpersonal conflict is internalized to the residents.5

Things

Things is a purchasing system, through which housemates access the house account. Residents can propose purchases, with bigger purchases requiring more upvotes to pass. Integrated directly into the house’s communications platform, residents are able to discuss, plan, and save for major purchases.

Monthly Circle

Not every practice needs to be operationalized through software. The Monthly Circle is an in-person check-in, through which housemates can vibe-set and find alignment on a wide variety of topics. This monthly low-tech practice complements and augments the “high-tech” tools used daily, creating a space to resolve novel issues not otherwise handled by the apps.

Creating a Social Contract

On a basic level, a collaborative coliving environment requires residents and management to believe in the possibility of positive-sum interactions, and be willing to coordinate behaviors in the service of a common benefit. This means co-creating and co-enacting a “social contract” over-and-above the transactional and often-adverserial relationship characteristic of rental housing.

There are many ways to create and sustain positive-sum relationships. Zaratan has operationalized this social contract in several ways: a shared house account, a welcome letter, and through financial engagement.

House account

The primary way that Zaratan operationalizes the idea of a “residents share” of value is by returning a percentage of base rent back to residents via a “house account.” Purchasing shared staples out of this account simultaneously lowers the effective cost of housing, gives housemates significant autonomy over their personal space, and internalizes the complexity of inventory management to the housemates.

Residents use these funds to buy cleaning supplies like dish soap and toilet paper, as well as food staples like eggs, rice, and oat milk. Chore Wheel’s Things app lets residents easily replenish shared supplies, or make special one-off purchases. Residents internalize the complexity of managing inventory, with Zaratan performing the low-complexity tasks of reimbursing housemates or placing bulk orders.

The (relatively) large shared fund creates a feeling of abundance, and lets residents directly access the surplus that they themselves co-create.

Welcome letter

When Sage opened in the fall of 2022, we deliberately avoided setting too many expectations. The concept was new, and we wanted to leave as much room as possible for residents to define and create their own experience.

This worked to a point. A number of early housemates had prior communal living experience and relished the opportunity to shape a space of their own. Things got rocky, however, when housemate priorities diverged from Zaratan’s, specifically around the planning of major projects.6

Recognizing the value of pro-actively managing expectations, we began sharing a “welcome letter” with new housemates, explaining the structure of the house and inviting residents to help co-create communal life.

Financial engagement

The power relationship between owners and tenants of land is one of the most well-studied, and fraught, in history. The son of a property-rights advocate,7 and having spent the last five years in Los Angeles’s real estate community, I understand the hostility with which society regards its landlords.

These dynamics can be improved, and while these fundamental power relations are bigger than any one project, it is possible to try and innovate at the margins.

One way Zaratan does this is by sharing some of the house’s financials. Housemates can see top-level accounts of expenses, debt, and revenue, and are periodically solicited for input when planning major expenditures. This practice puts prices into perspective, and makes it easier to dialogue with residents about sensitive topics like construction disruptions and rent increases.

Conclusion

In conjunction with the other models described above, “collaborative” coliving is well-suited to help solve some of the critical challenges of the day: social isolation and the high cost of housing.

Collaborative coliving promises more accessibility than grassroots coliving, while avoiding the high costs associated with managed coliving. It does so by engaging deeply with the political, social and economic dimensions of the housing relationship, in order to develop and adopt organizational forms which are better fit-for-purpose.

As Ben Horowitz famously said, “There are no silver bullets. Only lead ones.” Many of the institutional innovations deployed at Sage House could be easily, and incrementally, adopted by others. Chore Wheel is open-source and free-to-try, with ample documentation to help get communities up-and-running. Managed coliving operators could leverage these tools to help control their operational overheads. Grassroots coliving communities could incorporate these techniques, freeing time for more fulfilling activities.

The important thing is to experiment. As philosopher Karl Popper wrote:

It rests with us to improve matters. The democratic institutions cannot improve themselves. The problem of improving them is always a problem of persons rather than of institutions.

Housing exists at the intersection of myriad social, political, and economic forces, and creating and sustaining affordable, high-quality housing for millions will require ongoing innovation. Deepening our understanding of these forces and developing better techniques for managing them will help us achieve this essential goal.

When I was in leadership at the BSC, I had these printed and hung around the org.

Coliving management fees typically run about 10% of rents, vs 5% for regular multifamily.

Bungalow charges a service & cleaning fee of approximately $225 / month.

A notable counterexample is PadSplit, a public-benefit corporation which offers rooms-by-the-week to people making 80% or less of area median income. Seeking to offer a “pathway to financial independence,” PadSplit achieves this in part by offering few common spaces, imposing strict rules, and cultivating a spartan mindset among residents.

It is worth noting that PadSplit also incorporates a peer rating system into their operations.

Specifically, when we started work on Cactus Cottage in the summer of 2023. Housemates found the process disruptive and wanted scheduling decisions to be made collectively. Denying these requests resulted in some criticism and backlash.

My father and business partner, Robert Kronovet, made history in 2010 by being the first opposition candidate ever elected to Santa Monica’s notoriously partisan Rent Control Board.

This is pretty high level thinking, but the motivations you outlined for co-living resonate so much

- Structurally overcome feelings of isolation

- Decrease my housing costs (financial, effort, time)

I love Chore Wheel’s focus on making #2 a reality – I can see it as the “OS” for managed co-living that feels natural and easy.

For #1, I tend to engineer this through activities, but it requires so much intentional motivation to make it happen. I wonder if there’s an interesting opportunity there.

For example, I’ve integrated myself into the NYC surfing community and engage casually with this community every time I participate in the activity.

This doesn’t seem unique – co-living situations based on interest seem to dominate college campuses – houses exist for people who love to dance, are international students, are into engineering, are part of the same greek life organization, are sober, etc. etc.

However, I can’t filter based on resident interest on StreetEasy 🤣 Why? There are housing boards that exist that generally align folks with a vibe (i.e. listings project which aimed to connect creatives to affordable housing), and individual groups (like those out of Fractal, or even FB groups to find roomates) who help folks go through with this.

Apart from these groups being a fascinating distribution platform for Chore Wheel (i.e. how could Chore Wheel help manage the initial "looking for housemates" convo to create initial exposure to the tool?), I wonder if there’s something interesting around some merge between co-living, co-working, and hobby meetups?